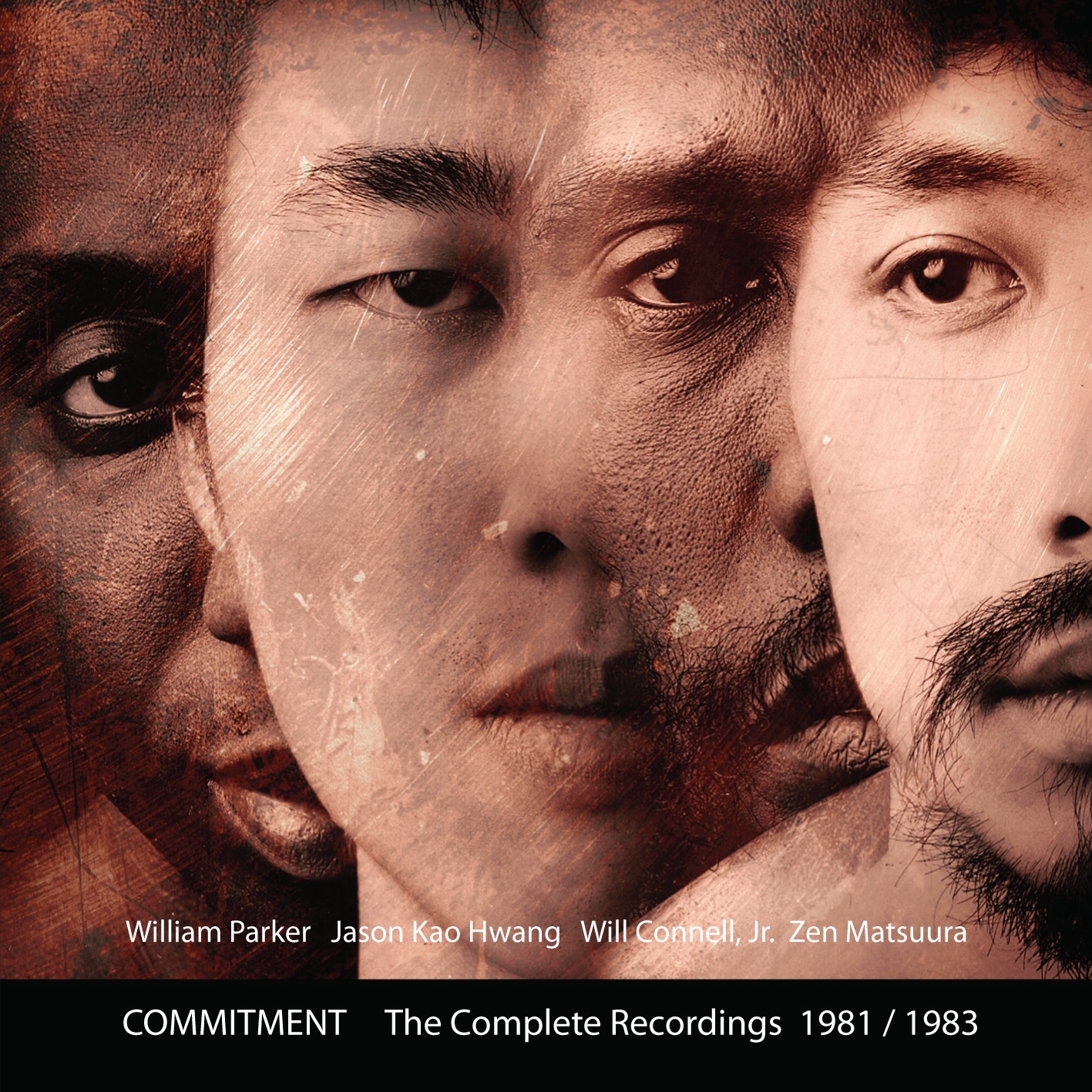

COMMITMENT

Will Connell, Jr. - flute, alto saxophone, bass clarinet

Jason Kao Hwang - violin, viola

Zen Matsuura - drum set

William Parker - string bass

Commitment: The Inclusive Landscape of the Soul

Liner Notes to the CD Commitment: The Complete Recordings 1981-1983

by Ed Hazell, 2010

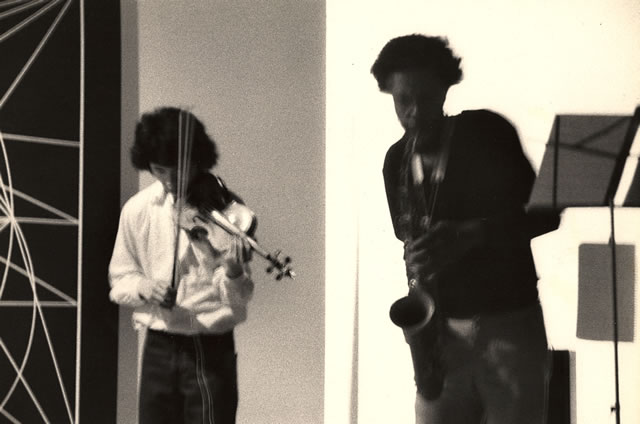

Commitment at the Hudson River Museum, 1982. Sirone on bass.

In some ways, Commitment – a collective quartet with violinist Jason Kao Hwang, reeds and flute player Will Connell, Jr., bassist William Parker, and drummer Zen Matasuura – was typical of many bands of their time. Between 1978 and 1984, they enjoyed a modest success by the subterranean standards of the Lower East Side. They struggled for gigs during the waning years of the New York loft scene, enjoyed higher profile gigs at several Kool Jazz Festivals, made one short European tour, and recorded one LP.

But their music is more significant than this story might indicate. Hwang was among the first improvisers to emerge out of the Asian American movement. His presence in the band as composer and improviser makes Commitment one of the first Afro-Asian free jazz ensembles. The presence of Asian American, African American, and Asian musicians in one band was almost unprecedented in the New York lofts, and their fusion of elements from Asian and African American cultures was unique. In these respects, Commitment plays an important role in the development of the music. (In San Francisco around this same time, Asian American improvisers such as Russell Baba, Gerald Oshita, Francis Wong, Jon Jang, Mark Izu, Anthony Brown, and many others were also creating a strong Asian American jazz scene.)

Certainly, Commitment was important for the development of the individuals involved. Hwang, energized by the burgeoning New York Asian American movement, began to understand his dual Chinese and American heritage and the musical implications of this identity. Connell found himself composing and improvising in one of the most sympathetic settings in which he ever performed. Drummer Zen Matsuura likewise found one of the most congenial settings in which he ever worked. For the first time, he could draw on his full range as a percussionist, showcasing his ability to play free pulse, his exceptionally musical approach to timbre and texture, as well as his swing and drive. The Commitment recordings are also essential documentation of the early evolution of Parker, who despite his active presence in the lofts as a sideman and as a leader, was not widely recorded at the time.

Several factors strengthened the artistic and personal bonds that made Commitment cohere into such an exceptional ensemble. It was a setting in which like-minded musicians could further refine and develop their ideas about the purpose and function of a collective improvising group. Hwang, who was only 21 when the band was formed, was being exposed to ideas about community-based art and artistic self-definition at the Asian American arts organization, Basement Workshop. Some of these ideas would influence his concepts of how a band should function and what it was for, how collective musical action could support personal empowerment and expression. Connell, with his experience in the community-based music of Horace Tapscott, was a veteran of putting these ideals into action and he helped crystallize the group’s collective concept. Community-building was also an important part of William Parker’s musical activity. His own projects were often rainbow coalition affairs, featuring men and women musicians, black and white, and he often welcomed visiting performers from Japan and elsewhere into his bands. For instance, a February 1978 performance of his composition for dance, “Kiva,” featured in addition to Parker, African American musicians Will Connell and Billy Bang, white musicians Rozanne Levine, Richard Schatzberg, and John Hagen, Asian American Jason Hwang, and Ryuichi Homma from Japan.

They also shared an interest in collaborating with artists who worked in other media. The Lower East Side lofts were a meeting ground for artists of all kinds, just as Greenwich Village had been a crossroads for painters, poets, and jazz musicians in the late ’50s and early ’60s. Commitment’s focus was always on the music, but their appreciation for other art forms fed into and enriched their performances. Zen had played for dance, theater, poets, and even a duet with a painter. Parker worked regularly with dancers, usually in collaboration with his wife Patricia Nicholson and other improvising choreographers. Commitment collaborated with Theodora Yoshikami’s Morita Dance Company and also, Jean Lee’s New York Chinese Dance Company. As an NYU film student Hwang was naturally interested in music and the moving image and recorded soundtracks with Connell for films by NYU faculty. Commitment also recorded one of Connell’s extended suites, “Shakti,” as a soundtrack for independent filmmaker Jon Wing Lum’s PBS documentary about Asian American women, To Be Ourselves. Hwang and Connell accompanied the Basement Workshop Poets, including Fay Chiang, Richard Oyama, Teru Kanazawa and Helen Wong. The widely read Connell drew inspiration for his compositions from a range of literary sources, including classical mythology. Both Parker and Hwang were poets and they frequent read during Commitment performances. “Jason was one of the first multi-dimensional people, in the sense of he was interested in film, poetry, and music and culture.” Parker says. “I remember Fay Chiang, you were crossing paths with creative people, it was like a family, a loose family that was strolling down this long, creative path together and everyone had their individual sensibility. It was like everyone was the same, but recognizing that individuality, everyone could co-exist. Everybody did what they had to. You come together, you part, you come together again, because everybody has to do what they have to do.”

They held in common one other life experience that consciously or unconsciously formed a bond among them – racial prejudice. It goes without saying that it was an everyday fact of life for African Americans as well as Asian Americans. Zen experienced it in two cultures. His father was Korean and his mother was half Korean and half Japanese. Consequently, he endured quite a bit of ethnic prejudice growing up in Japan. After he moved to New York and as he began touring Europe, he found that some presenters said they wanted to see a black man on drums. They felt it would be more “authentic.” “It has been painful to worry that my ethnicity could be perceived as a detriment to the vision, quality, or authenticity of music,” he says. “Music was the only place that prejudice didn’t play a role in my development in Japan, but white Westerners were having a problem with it, I think mostly businessmen. I’ve learned there’s a difference between racism in Japan and in Europe and America. Japanese prejudice is ugly by its very nature, but it never prevented Koreans from earning a living, having an excellent education, or having decent living conditions. The West’s racism literally deprives people not only opportunity to work in the mainstream, but to work anywhere! Racism in the West actually seems to prevent people of color from having access to the basic necessities of life.”

Jason Kao Hwang: We Were One of Only Two Chinese Families in Town

Jason Kao Hwang, circa 1979.

A first generation American of Chinese decent, Jason Hwang grew up near Chicago in Waukegan, Illinois. His father, Dr. Kao Hwang, had immigrated to the States from Hunan on a Tsing-Hua National scholarship, created by the U.S. from Boxer Rebellion indemnity funds, in 1945. Immigration from China had been nearly impossible since 1882, thanks to xenophobic Chinese Exclusion Laws enacted in response to Nativist fears of a large emigrant Chinese labor force “stealing” American jobs. However, the U.S. and China were allies in WWII, and FDR significantly eased restrictions. Dr. Hwang left behind Sheila, the woman he loved and they were not reunited in the U.S. until 1948, when at last they married. They had four children, including three daughters, Leila, Miriam, and Catherine. Jason, born in May 1957, was the youngest and the only boy. “When I grew up, we were one of two Chinese families in town,” Hwang says. Untroubled by the cultural divide he straddled, he began violin lessons at age 8 in the Waukegan public school system, graduated from Highland Park High School, where they had subsequently moved, and enrolled at NYU as a film student in 1975.

For a student with precocious, if unfocused, artistic abilities, it was an exciting time to be in New York City. The loft movement was at its height and NYU, situated just west of Broadway and south of 14 St., was within blocks of many of the most active loft spaces, such as Studio Rivbea, Ladies Fort, and Ali’s Alley. Musicians papered walls and telephone poles with flyers announcing gigs, and walking down the street was often a better way to find out what was happening than reading the Village Voice. In 1977, a flyer in the East Village Bookstore caught Hwang’s eye. It advertised not a loft gig, but a poetry workshop at an Asian American cultural center, Basement Workshop.

Basement Workshop: Wrestling with the Question of Asian American Identity

Around 1971, a group of Asian American political activists and artists in New York began working together to address social and cultural issues in their respective communities. They knew each other through their activism in the anti-War movement or through participation in campus Asian American ethnic, women’s, and gay studies programs. “Wrestling with the question of Asian American identity and a place in this society, forced many of us to question what was happening with this country domestically and with its policies abroad,” long-time director Fay Chiang says in Basement Yearbook 1986, a personal history of the organization.

Under Chiang’s energetic direction, Basement Workshop offered classes, workshops, and performances in poetry, dance, children’s arts, and folk arts, as well as community service programs, first at 22 Catherine St., and later at 199 Lafayette St. Nor were the programs confined exclusively to Asian Americans. “Connections with artists, arts service organizations in the other minority, ethnic, alternative and experimental spaces broadened our audience and created greater visibility for Asian American artists in New York and nationwide,” Chiang writes.

“I went there for the poetry workshops and met other American-born Asians there for the first time,” Hwang recalled. “So a lot of my political awareness came from Basement Workshop, especially regarding the construction of Asian American culture. Here was a group of artists dedicated to writing their own history and their own music and trying to define themselves on their own terms in a more honest and broader way.”

Connell had many occasions to observe the activity at Basement Workshop and found a familiar spirit in the charged, creative atmosphere. “To me, it was almost like the ferment in Watts in the 1960s,” he says. “I was watching people come into their own, beginning to understand the beauty of their own cultural heritage. As well as coming to grips with the racial and cultural situation in America. They were coming out of the same set of energies, but relative to them, to Asian Americans.”

At their 199 Lafayette St. location, Basement Workshop held a Sunday afternoon jam session hosted by guitarist Geoff Lee and pianist Kuni Mikami. At one of these jam sessions, Hwang first met Connell, whose knowledge of the loft scene would make him a major catalyst in the formation of Commitment. Connell had heard about the jam session through the musician grapevine. “There was this horrible little bar called the Kiwi on 9th St. that had a jam session,” Connell remembers. “Stanley Turrentine’s brother, Tommy, lived in the neighborhood and played there sometimes. So I thought because it was just a neighborhood thing, I could go hear Tommy. When I go there, Roy Nathanson is running the jam session, looking like Frank Zappa and wearing motorcycle boots. There was a piano player named Kuni Mikami and he said there’s another jazz session at an Asian American workshop over on Lafayette.

“So I go there, and it was this big loft,” he continues. “And there was Jason standing there in a pillar of sunlight, looking like the angel Gabriel. The jam session hadn’t started yet. He was just soliloquizing with himself. The next thing I knew, the flute was out and we were singing together and that was it.” Connell may be mythologizing that first meeting a bit, but there’s no question that the veteran reed player and the novice improvising violinist hit it off.

After their initial meeting at the Basement Workshop jam session, a close bond developed between Connell and Hwang. “I would go over to Jason’s house and sit with my flute on my lap until he stopped doing his homework—he was still at NYU—and pick up the violin and we’d play.” They performed as a duo with Basement Workshop poets and on soundtracks to a few films, including NYU film professor Pat Cooper’s short film, To a Darker Kingdom. Connell also collaborated with Hwang on his poetic documentary, Afterbirth, later shown at the Museum of Modern Art. It is has recently been re-issued as a DVD by the Center for Asian American Media.

Early on, there was a student-mentor aspect to the relationship, which has since matured into a peer relationship. ”Will introduced me to music, musicians, the meaning of music and a band, and the revolutionary power of ensemble improvisation. He also introduced me to William and Zen. I am grateful to Will for opening the door to music for me, with all his wisdom and integrity,” Hwang says of those early years.

Will Connell, Jr.: No More Energy for the Devil

Will Connell, Jr.

Connell had moved to New York from his native Los Angeles in 1975. Born in November 1938, Connell and his family were one of the first African American families in the Liemert Park/Baldwin Hills area of L.A. when they moved there in 1950. Connell entered the Air Force immediately after graduating from Dorsey High School, whose alumni also include Eric Dolphy and Azar Lawrence. Trained as a weather observer and mapmaker in the service, Connell was stationed in Korea and elsewhere.

While in the Air Force, Connell had an accident that helped turn his attention to music. “I was stationed in eastern Turkey and had an accident filling the weather balloon with hydrogen.” Connell says. “I wasn’t wearing the safety goggles and for 48 hours, I didn't know if I was ever going to see again. During those sightless hours, I said to myself, ‘I don’t want to be old and wish I had tried to play some music.’ When they unbandaged one eye, I started reading every book about music I could find. That's how it started. I always say I didn’t see the light, but I felt the heat.”

Eventually, his moral qualms about the military, his new-found interest in music, and a growing sense of political outrage led him to leave. “I had been almost nine years in the Air Force and I finally said, no more energy for the devil,” Connell recounts. “I wanted to aide human evolution on some kind of broad scale. It was about that. Being an only child, being part of a community was very fulfilling, rewarding. I always wanted that more than anything else.”

Back in L.A., Connell was further radicalized by the events of the Watts Uprising of 1965. Residents of South Central L.A. were already seething at the high unemployment rate, poor housing, bad schools, and poverty endemic to the area, when a confrontation between a white policeman and an African American motorist at a routine traffic stop took on racial overtones and provided the spark that ignited six days of rioting that left 34 dead. Despite a California commission report that clearly identified the causes of the people’s anger, little or nothing was done to help the neighborhood. The violence and its aftermath threw the black community on its own resources and deeply alienated the Watts area from mainstream culture.

Connell’s countercultural leanings, commitment to noncommercial music, and community focus drew him inevitably into the orbit of pianist Horace Tapscott, who, partly in response of the events of 1965, had established the community-based musician’s collective, the Union of God’s Musicians and Artists Ascension (UGMAA) and the Pan African People’s Arkestra (PAPA) big band. He was closely involved with Tapscott’s many musical projects from 1967 to 1974. “I was a trained weather observer and plotting the weather is meticulous work. So one day Horace saw me listening to the Brandenburgs and reading along with the score, and he says c’mere, I know what to do with you. And he made me a copyist. I got trained at the shop where Motown did the majority of their stuff out there. I either worked or hung out there and I played alto and did the library work for Horace.” At the Motown shop, Connell worked as copyist for Stevie Wonder, Roberta Flack, Michael Jackson, Simon and Garfunkel, and others.

For a period, the Arkestra rehearsed at Connell’s home. Sections rehearsed on different weekdays and the entire band came together on Saturdays in the small front room of Connell’s house on Fifty-Second Place. With the full orchestra in attendance, “we’d have to tape music to people’s backs to read it,” Connell told author Steven L. Isoardi in The Dark Tree. Connell was also a member of the collective Free Form Quintet and the leader of a sextet, both of which included other UGMAA members.

In New York, Connell was content to work behind the scenes as a copyist and to play only occasionally. “I tell you the truth, I came to New York because I wanted to be a hermit. And practice,” Connell says. But since he moved to New York, Connell has not been entirely a hermit. In 1976, he recorded as a sideman on Chico Hamilton and the Players, a Blue Note album that also featured his former Tapscott band mate, Arthur Blythe. He played in various William Parker ensembles, including the Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra, the Cecil Taylor Orchestra, and Steve Swell’s N.O.W. Ensemble. He also performed with Sam Rivers, David Murray, Anthony Braxton, Butch Morris, Pharaoh Sanders, Roy Campbell, Billy Bang, and many others. He’s used the copyist/arranger skills that he honed with Tapscott working on scores for Julius Hemphill, Henry Threadgill, and Ornette Coleman’s Skies of America. Nothing if not versatile, he also took popular-music jobs with Elton John and Ryan Adams.

First Rehearsals

At the Basement Workshop jam sessions, standards and jazz originals were the order of the day. More avant-garde music was frowned upon, despite the fact that many new jazz players were often participants. At Connell’s instigation, he and Hwang began rehearsing with two other jam session participants with more avant-garde leanings – drummer Denis Charles and bassist Jay Oliver – in the first incarnation of Commitment.

Beloved by musicians for his joyful spirit and positive personality as well as his drumming, Charles was returning to music after a long absence. In the early 1960s, he had played with Cecil Taylor, Sonny Rollins, and Steve Lacy (among others) before getting sidelined by personal problems. From the late ’70s until his death in 1998, he enjoyed a remarkable renaissance, playing and recording with William Parker, Billy Bang, Jemeel Moondoc, and countless others on the Lower East Side jazz scene.

The original quartet never performed publicly. Shortly after the first rehearsals, Charles’ busy schedule made it hard for him to continue with the group. Commitment became a trio with Oliver playing both bass and drums.

The Bluest J

Although best known as a bassist, Jay Oliver was also an accomplished drummer. In the mid-’70s, he had moved from San Francisco to New York, where he was active in the lofts. In January 1979, he and William Parker played duets at Someplace Nice, a cultural center at 93 St. Marks Place run by community activist John Dahl. Oliver was also a member of the all-star Big Moon Ensemble – featuring Jemeel Moondoc and Daniel Carter on saxes, Roy Campbell and Arthur Williams on trumpets, Denis Charles and Rashid Bakr on drums, and Parker and Oliver on basses – whose May 1979 concert is the stuff of Loft Era legend.

The crushing neglect that is routinely the lot of jazz musicians eventually drove Oliver from New York, despite his enormous talent. In the liner notes to Sunrise in the Tone World (AUMFidelity), Parker remembers Oliver, to whom he dedicated a Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra composition, “The Bluest J.” Oliver “could not find enough work in his native land to raise a family,” Parker writes. “Fed up with both the politics of America and the ‘jazz life,’ Jay departed from the United States in the spring of 1980, first living in Zurich, and later moving to Berlin.”

Even in Europe, he recorded and performed with Jimmy Lyons and in a quartet with Alexander von Schlippenbach, Sven-Ake Johansson, and Rudiger Carl. Jemeel Moondoc also tapped him for the bassist on Muntu’s final European tour in 1982. He made only one album as a leader, Dance of the Robot People(Konnex), with Steve Lacy, Glenn Ferris, and Oliver Johnson in 1981. Plagued by lung and heart problems for many years, he died of a heart attack in March 1993. “Jay loved people,” Hwang recalls. “He was a warm person with an easy, hearty laugh. He was also tough. Despite his struggles in New York, he never projected his frustrations to the band or other friends. Jay always brought sincerity and spirit to the band stand.”

First Gig

The trio played the first public Commitment gig at the Ladies Fort on September 7, 1978. Connell walked into the offices of the Village Voice and presented their jazz critic, Gary Giddens, with a copy of the flyer advertising the debut, urging him to publicize the gig. The personal touch worked. Giddens ran the following notice in the Voice Choices column: “I’ve heard Will Connell play fine alto with Chico Hamilton and he assures me that the violinist in this trio, Jason Hwang, is terribly good. The third member is bassist/drummer Jay Oliver.”

“I remember Ladies Fort,” Hwang says. “I made $15, which was exactly enough to buy a red hand truck so I could wheel around my Polytone amp. I would wheel that thing from my place on 6th St. all the way to Jay’s place on Elizabeth and Houston.” Connell remembers that his former Tapscott band mate, Butch Morris, was in the audience, as well as Henry Threadgill.

After Oliver departed for Europe, the band needed a new bassist and drummer. Connell suggested bassist William Parker, with whom both he and Jason had played on several occasions, to join the group.

William Parker: Music and Art Can Heal People

William Parker, circa 1979.

Parker grew up in a housing project in the Bronx. His father Thomas was born in North Carolina and worked at a variety of jobs over the years, including a furniture store, an undertaker’s, and a bakery. His mother Mary, one of twelve children from a South Carolina sharecropping family, worked in a public-school cafeteria. A serious, artistically inclined teenager, Parker read Eastern philosophy and the Bible, and poets like Kenneth Patchen. He was attracted to the films of Stan Brakhage and other avant-garde filmmakers. He wrote plays, essays, and poetry of his own. However, the music of John Coltrane and Albert Ayler inspired him to pursue music.

“When I was in high school I realized the music had a value,” Parker said in an interview with Signal to Noise editor, Pete Gershon. “That, really, what it was all about was that music and art can heal people, and sort of uplift and enlighten people. And I thought that I could participate in that process, so I decided to become a musician. You see, it was only after I decided I could participate and make a statement like that that I decided to become a musician and jump into the area of free music or avant-garde music. I thought that was my calling, so to speak, and I began to study the bass.”

Parker has achieved the widest recognition of the members of Commitment. His tenure with Cecil Taylor in the ’80s is well documented on record, and he’s been widely recorded as a leader since the early ’90s. But little of his prolific activity in the ’70s is documented. Parker was an almost ubiquitous presence in the lofts as both a leader and a sideman. In Sound Journal, he describes a typical day for him during the loft era.

I walk to 11th St. and Ave. B to a place called the Firehouse, an old fire station now owned by a saxophone player called Juice. I play in his quartet. We rehearse every day at 10 a.m. to about 1 p.m. … At 2 p.m. I leave the Firehouse and head to 193 Eldridge St. for Studio We, where I play with Juma Sultan’s Aboriginal Music Society and in the We Music House. If I am not at Studio We, I’d head to Chambers St., where Cecil Taylor is rehearsing a large ensemble; players such as Jimmy Lyons, David S. Ware, Raphe Malik, and Karen Borca are in this ensemble. These rehearsals go until about 7 or 8 in the evening.

Each evening I would head to Studio Rivbea, 24 Bond St., a living loft run by saxophonist Sam Rivers and his wife Bea. Music was presented 7 days a week. For a period I was playing 4 to 5 of these nights with different bands. On Tuesday evening I played with Charles Tyler’s band: Earl Cross, trumpet; Steve Reid, drums; Charles on baritone sax (Charles was also in Cecil Taylor’s ensemble.)

Parker also worked in bands such as Jemeel Moondoc’s Muntu (whose early recordings are reissued by NoBusiness), the Melodic Art-tet (with Charles Brackeen, Ahmed Abdullah, and Roger Blank) and ensembles led by Billy Bang, Frank Lowe, David S. Ware, Don Cherry, Sunny Murray, and many others. He and Bang, along with drummer Roger Baird, multi-instrumentalist Daniel Carter, bassist Earl Freeman, and trumpeters Malik Baraka and Dewey Johnson were members of the little known free-improvisation band, the Music Ensemble, whose work wasn’t documented until 2001 on a self-titled CD released by Roaratorio. He was also a composer and leader of a wide range of ensembles. He wrote and performed extended suites for large ensembles, including Nascent: A Peace (sic) for Dance and Music(1975) and Sun Garden (1977). For smaller groups, he wrote and performed music for dance, includingDocumentum Humanum (1976), Dawn Voice (1976), Liberation Folk Suite (1977), and many others.

Zen Matsuura: There Has Always Been a Drummer in Me

Takeshi Zen Matusura, circa 1979.

Connell also asked drummer Zen Matsuura to join. Zen was born in Kobe, Japan, but grew up in Tokyo. As a teenager, he felt little hope for his future because of the pervasive Japanese prejudice against Koreans. His father, who moved from Korea to Japan for college, had managed to establish his own Pachinko machine business. His mother, whose father was Korean and mother Japanese, ran a successful restaurant. “They wanted me to have every opportunity possible,” Zen says. “They wanted me to naturalize as a Japanese citizen and give up my Korean citizenship. By wanting me to be secure, my parents sort of separated my identity from theirs. It was a very confusing time for me and I expressed my confusion by acting out and rebelling against the Japanese system. So I got kicked out of high school, which in Japan is a really serious thing.

His uncle Tomio Toyama, a successful architect and a jazz lover, took the troubled kid under his wing. Among other things he did for Zen, he gave him a book with biographies of Charlie Parker, Clifford Brown, Monk, and other jazz greats. “He told me to listen to Parker, but it was a little too difficult for me at age 14,” Zen remembers. “Then I heard Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers with Lee Morgan and Bobby Timmons, and it pulled me right in because it sounded so warm. He not only saved my life, but he gave me my life – which from then to now has been jazz.”

His uncle persuaded Zen to give high school another chance. This time, he embraced school and it embraced him back. He made new friends, including Hiroshi Fukumura, a trombone player who later worked with Sadao Watanabe. They spent all their spare time in jazz coffee shops, popular hipster hangouts that played all the latest Western music, but jazz in particular. “I started studying drums,” Zen says, “and really, there has always been a drummer in me. I drove my parents crazy as a boy by banging on everything I could get my hands on. I began asking friends in the school band to hustle me up drum sticks from the music closet.”

In the 1960s, there were no jazz schools in Japan. His mother, who was always “my fundamental supporter,” Zen says, sent him to Mr. Oyake, a well-known percussion teacher at the prestigious Gedai University, later known as the Tokyo University of the Arts. “I remember feeling I needed to tell him that I wasn’t Japanese, and ask him if it was okay for me to audition,” Zen says. “He didn’t hesitate to tell me that it shouldn’t effect an individual’s talent.”

Zen was one of only three percussion students accepted that year. “I basically did what I wanted to do in college,” Zen continues. “I was being classically trained but I was always practicing trap drum. In fact, I based my final graduation recital on Max Roach’s drum solo from Drums Unlimited. Those were sweet years, filled with lots of hope and promise, but also a lot of political upheaval.”

Tokyo University and TUA were at the forefront of the Japanese student protest movements of the 1960s. Passions ran very high; students were killed in some of the demonstrations. Most protests focused on Japan’s support of U.S. nuclear proliferation (memories of Hiroshima and Nagaski were still fresh) and Japan’s hosting of U.S. military bases. Ironically, it was U.S. army musicians who helped Zen in the next stage of his career.

“I was playing in jazz the clubs and often I worked with pianist Takehiro Honda, and later with Hideo Ichikawa, who made nice albums with Jack DeJohnette and also Joe Henderson. One night, a friend of these American soldiers asked by if I would play with their soul band. I thought why not? I loved soul music and it was also an opportunity to play with Americans – African Americans. We played all the hottest music at that time – Aretha Franklin, James Brown, New Birth, Al Green. I really got to open up my expression in that music and those guys were very supportive of me. I was meeting more and more American musicians, so playing Japanese clubs just wasn’t enough for me anymore.”

In the early ’70s, Zen moved to New York and eventually found the ideal apartment on 6th Street in the East Village. He could practice without disturbing the neighbors and he found himself in a music and arts mecca. Blood Ulmer lived across the street; Gylan Kain, one of the Last Poets, lived down the block; around the corner lived pianist Gil Coggins; and a few doors from Coggins, lived Saint Strickland, a painter and multi-instrumentalist who became one of Zen’s closest friends. “It seemed like there were no closed doors, literally!” Zen recalls. “There was always a gathering of some type at someone’s apartment. I really loved working with Gylan Kain, his work was so current, so deep, raw, and intelligent. We usually worked in a trio with Saint Strickland on the electric piano, and we always played to a packed audience. I met my wife Tanya on 6th Street, she was both an actress and a dancer back then. It was the neighborhood of my dreams.”

I really enjoyed the freedom to practice in my space on 6th Street, so I practiced all the time,” he continues. “It was a basement apartment, and the next thing I knew people were knocking on my door, asking me to jam with them, or telling me I sounded great, or inviting me to a creative gathering. I felt like I really belonged here, and there was no sting of racism or ethnic prejudice, although people were sometimes surprised that the guy on the other side of the door was a Japanese cat. One day, Frank Lowe and Butch Morris knocked on my door. They had a gig at Ali’s Alley and asked me to play. That was my first step into the free music style of jazz. At first I thought, I can’t play this kind of music! But, it’s one of those strange things that happen in life – that music just kept coming to me. Every knock on my door was from musicians who played avant-garde or free music. I began playing more and more in that style, with people like Roy Campbell, Billy Bang, Sirone, Zane Massey, a guitarist named Masujaa, Bryan Carrott, Ahmed Abdullah, Reggie Workman, and others.

“Then one day Jason and Will came together and knocked on the door. At first we just jammed at my place. Later, they brought William Parker over and I remember that as soon as he hit one note on that bass, I knew that he’s going to be our bass player.”

We Hit the Loft Scene with a Passion

Jason Kao Hwang + Will Connell, Jr., Open Gallery Gary Halpern©1980

With a stable band assembled at last, Hwang and Connell began lining up gigs. “We hit the loft scene with a passion,” Hwang says. There is documentation of gigs at lofts such as Inroads, Sha-Sha House, and Ladies Fort, and there were undoubtedly others. At the Universal Jazz Coalition, they were part of the first Asian American Jazz Festival organized by Cobi Narita in 1984. Commitment usually rehearsed in Zen’s storefront apartment on East 6th St, just down the block from Hwang’s apartment. For extended ensemble projects, Commitment sometimes rented the 12th Street rehearsal studio of Air, the collective trio of Henry Threadgill, Fred Hopkins, and Steve McCall. And of course, a few new concert spaces were always cropping up. Commitment had many gigs at the Life Café, a coffeehouse at 10th Street and Avenue B that opened in 1980. It was operated by Kathy Kirkpatrick and artist David Life, who later became a yogi who founded and still runs the Jivamukti Yoga Center in Manhattan. Life Café hosted musicians like David Murray and John Zorn, but is most widely known as the setting for “La Vie Boheme” in the musical Rent. Gigs at the Open Gallery in 1980 and the Museum of the Night (30 W. 21st St.) in 1982 are also documented.

The loft scene, however, was in decline. By 1980, Studio Rivbea, Ali’s Alley, and Ladies Fort were no longer in operation. The low rents that attracted artists and musicians to the Lower East Side were on the rise, forcing out existing lofts and curtailing the establishment of new ones. Places to play, already scarce for avant-garde bands, were becoming even harder to find.

Besides the crumbling loft scene, other factors circumscribed opportunities for a young band like Commitment. Many of the players who had paid dues in the lofts were now established enough to play in some of the new clubs that were opening, such as Sweet Basil, Fat Tuesday, and Lush Life. But these clubs were unlikely to take a chance on an untested band like Commitment. Federal arts funding was more plentiful than ever before, and nonprofit series, such as the one at the Public Theatre offered high-profile gigs to loft-jazz veterans, but they too presented more established artists. European festivals grew in number and importance, but making connections and juggling logistics of overseas travel were daunting. And while European jazz labels, most notably Black Saint/Soul Note and hat Hut, documented many of the best American groups, self-production remained the best, sometimes only, option for bands with lower profiles. Tastes were changing and audiences were increasingly attracted to a new generation of more conservative – and heavily marketed – musicians, of whom Wynton Marsalis was the most prominent.

Soundscape

Commitment did find a haven at Soundscape, a loft space operated by ethnomusicologist Verna Gillis, one of Commitment’s strongest advocates in New York. Between 1979 and 1984, Gillis presented both established musicians as well as emerging composer/musicians at the eighth-floor loft at 500 West 52nd St. Reflecting Gillis’ academic training, special emphasis was placed on music from around the world and their fusions with jazz. “Its musical consciousness features artistic freedom, experimentation and curiosity about what happens when music and cultures mix,” Robert Palmer wrote in a July 9, 1982 article in The New York Times.

“Soundscape’s mission was specifically for groups like Commitment – they knew they always had a space where they could perform,” says Gillis. “I thought that Commitment was special in many ways; their conception was unique and the music was always compelling. And not a small thing – they were all lovely humans in addition to being serious and great musicians. It was a pleasure to deal with them – and that is a big thing when dealing with so many difficult personalities.”

Soundscape offered Commitment many opportunities to perform over the years, including an ambitious program in April 1982, working with a large ensemble that included five additional string players, three woodwinds, and a vocalist. Gillis also showcased the band in New Music concerts she produced for the Kool Jazz Festivals in 1981, 1982 and 1983. In his New York Times review of the 1983 Kool Festival concert, which also featured Mario Rivera and the Salsa Refugees’ Merengue Jazz, Jon Pareles wrote, “The quartet has the rare ability to give drama and direction to music with a floating beat, and its main soloists – Jason Hwang on violin and Will Connell, Jr. on woodwinds – chose every note with care.”

In the face of the rather long odds, Commitment’s personnel remained mostly stable. On the rare occasions that Zen was unavailable, Denis Charles subbed for him. A replacement for Parker was needed more frequently, as he became increasingly busy with Taylor. For example, Parker was in Paris with Taylor on November 6, 1981 when Billy Johnson, a bassist whom Hwang knew from Dr. Makanda Ken McIntyre’s CAAMO (Contemporary African American Organization) Orchestra, subbed for him at a Soundscape gig. In the summer of 1982, Sirone performed with the quartet as part of a music series produced by Soundscape at the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers. (Connell remembers it because “It was our first $100 gig!”) Fred Hopkins played bass at the 1984 Universal Jazz Coalition Asian American Jazz Festival.

The Commitment LP

Shortly after the personnel solidified, in October 1980, Commitment went into the studio to record the only album they ever released. (They recorded a second album in 1984, but were unhappy with it and never released it.) Gillis once again played an important role in the band’s story. Gillis offered to set up free studio time at a radio studio for Commitment to record an album. The band accepted her offer. Commitment’s self-titled LP, the only release on Hwang’s Flying Panda label, is a forgotten masterpiece of the final years of the Loft Movement, an album containing substantial music of great originality and emotional depth, brimming with ideas that still sound fresh and radical today.

The brilliance of the ensemble playing is the first thing that strikes the listener. For instance, the unison reading of Connell’s “Mountain Song” unbraids into four independent improvised lines without ever losing a sense of unity. No solo statement overshadows the mood established by Hwang’s “Grassy Hills, the Sun” or its collective development by the band. On Parker’s “Famine,” the horns move in close formation as they unfurl long tones whose colors and textures they manipulate and transform. The seamlessness of these tracks, the attention to shaping each performance into an organic whole, is a hallmark of Commitment’s conception. The tempos are often slow, yet the band maintains a sense of forward movement and structure. As Pareles noted in his short review of the album, “Commitment is one of those abstractionist bands that makes you forget you’re listening to separate instruments as the music pulses and twines.”

The album is also a showcase for the soloists’ improvisation. Connell is an inherently orderly improviser, whose sound and swinging phrasing owe a debt to West coast bebop. On “The Web of Forces” and “No Name,” his solos proceed inexorably from initial idea to extensions and variations, but his openness and spontaneity keep his solos fluid and flexible, and the vocal quality of his sound gives these gracious improvisations a deep humanity.

You can hear the jazz tradition in Zen’s playing, too. His snare accents and cymbal work on “The Web of Forces” and “Grassy Hills, the Sun” sound as if they were passed down from bebop drummers like Max Roach and Kenny Clarke. But he had moved to New York to play in situations where he could expand his horizons and he is equally capable with free pulse and energy. Compositions such as “Famine” and “Mountain Song” reveal his attention to texture and timbre, as well. The Commitment LP remains the most complete showcase of the full range of his ability.

By the time of the recording, Parker had developed a unique approach to the bass. It is unschooled in the best possible way. It’s a style that is lived, not learned; it could only emerge from within, never from a classroom, and only be perfected through long playing experience. On “The Web of Forces” and “No Name,” he combines great energy and movement with tremendous strength and stability. Everything is in motion, but there’s not a sense of instability; everything feels strong and secure. His lines maintain continuity through repetition and small variations, even as they jump between registers. But the lines are always pushing ahead; the structure he creates evolves spontaneously with the music. His timbre on “Famine” is also changing as the music progresses, as if filtered through prisms that highlight different parts of the sound spectrum.

Hwang’s playing is just as unprecedented. He has shorn his music of overt influences and synthesized them into an entirely personal musical vocabulary. Much of it is taken from the jazz tradition in which he is working, but on “Web of Forces” and “Grassy Hills, the Sun,” you can hear how elements from classical music and the music of China and Japan give his playing a time feel, sense of line, and a palette of colors and textures that is completely unique. Sometimes it may be nothing more than the way a note is inflected, or an awareness of space or asymmetry in a line. There is no see-sawing between jazz and Eastern and classical influences, they are all present in the music at once. The same is true of Hwang’s composing. “Grassy Hills, the Sky” is only equivocally Chinese, there is no attempt to accurately reproduce Chinese elements, instead they are absorbed into a personal context.

This context is reflected in the liner notes for the LP:

What we call ourselves is what we, like many musicians, strive to be.

Commitment is the spirit and the tradition of music.

To feel and recognize commitment in your life, towards your individuality,

Is a revolutionary act within the fabric of today’s society.

The tradition is revolution because the tradition is love—

Sidney Bechet, Charles Parker, Billy Strayhorn, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy,

Dewey Redman—this is the tradition we encourage and hope to express.

We wish to celebrate music with you.

Musical culture has evolved to an historical point where jazz is played,

swung and heard around the world. These recent phenomena illuminate

the true depth of the musical spirit—the inclusive landscape of the soul.

Music is a healing force.

The soul of jazz is deeper than the artifice of appearance—that dead fruit

of increasingly sophisticated marketing strategies which alienate music

from musicians and listeners alike.

The tradition of music has survived a history of economic and cultural

oppression because it’s spirit has a life independent of artifacts.

This allows music, jazz, to grow into a commitment of international character.

When we, as a family of musicians, play

and you, who listen openly, meet

we will explore the face of soul—it’s the tradition.

Looking forward.

Europe 1983

Jason Kao Hwang with Commitment at the Groningen Jazz Marathon

Anko C. Weirenga©

In the spring of 1983, Commitment made a brief sojourn to Europe. On May 20, they performed at the 11th Moers Festival in the echoing Moers Eissportshalle (roughly translated as Ice Sports Hall; it was essentially a hockey rink). They were the opening band on a bill that also included Duck and Cover, an international group that included Fred Frith, Heiner Goebbels, Alfred Harth, Dagmar Krause, George Lewis, Chris Cutler, and Tom Cora; the Odean Pope Trio; and the Golden Palominos. The next day, they performed at the Groningen Jazz Marathon in Holland.

The concert recording from Germany is both an indication of how strong Commitment’s group conception was and how far they could push it. Although not a studio-quality recording, the tape is a genuinely important find – it’s a terrific performance. This was the first time in Europe for everyone in the band except Parker, and you can hear how excited they are. From the opening notes of “Ocean” with Hwang and Connell entwining their singing tones and the deep throb of Parker’s bass meshing with Zen’s distant-thunder mallet sound, the band is energized. Connell uses the theme as the basis for an especially melodic improvisation, goaded on by Zen’s insistent groove. Hwang’s solo is among his best on record. He sets up a call and response between registers on the violin, with saw-tooth phrases, both bowed and plucked, crosscutting the beat with increasing urgency. The entirely improvised “Pathway” indicates that the energy level is not harming the ensemble sensitivity and balance that is so essential to their concept.

“Diary for One at Night” is another example of the band’s individual and collective brilliance. Connell spins out variation after variation on a tight cluster of notes played in tense rhythmic groupings that grow increasingly exciting through repetition and extension, creating a narrative thread that leads far from the initial starting point. Hwang’s solo once again displays the maturity of his approach. His lines push and pull forcefully in different directions, creating a unique sense of space and rhythm that swings, but in a highly idiosyncratic way. The Chinese flavor in his music is just there in the sound, not grafted on to it, but living in it, not imposed on the jazz elements but somehow emerging from within them. Parker’s solo bursts out of him in a rush – one phrase seemingly begins for the preceding one ends.

“Continuous” describes an arc of rising tension and intensity. Parker’s tolling bass notes and Connell’s nocturnal bass clarinet introduce the piece before the heartrending melody is played. Parker’s embellishments of the theme push up the energy level from below until he and Zen snap into tempo. Connell’s flute solo skitters and darts like bird song and Hwang’s lightning quick bowing and rapid changes in color and texture climax in a marvelous collective passage.

The version of “Grassy Hills, the Sun” may be the definitive recorded version. They play the theme with close attention to dynamics and phrasing and the collective improvisations have a composerly unity. Connell pushes his thematic improvisation to far limits of abstraction and coherence, and the sobbing cry of his tone is riveting. Parker’s solo is patiently linear, making frequent reference to the composition, and played with a dark, woody tone. During Zen’s solo, his brushes snap and percolate between a continuously evolving bass drum pattern below and a delicate wash of cymbals above. The final collective, played with great clarity and warmth, swells to a mournful, compassionate climax. The encore, Parker’s “Whole Grain,” is a brisk closer that ends the concert on an upbeat note.

After their return from Europe and their appearance at the 1983 Kool Festival, the band was far less active. Only one appearance at Soundscape in February 1984, the Asian American Jazz Festival, and a set at the Sound Unity Festival in June of that year are documented. As far as can be determined, the Sound Unity Festival, which was singled out in Village Voice coverage of the event, was their final gig.

Of course, Hwang, Connell, Parker, and Matsuura all remained active after the end of Commitment. Hwang went on to lead several of his own bands, including The Far East Side Band, Edge, and Local Lingo, a duo with kagayum player Sang Wong Park. He also composed a critically acclaimed opera, The Floating Box: A Story in Chinatown. Connell performed in various large ensembles and is a member of the composer’s collective Silverback, featuring Frank Lacy, Newman Baker, and Hilliard Greene, and occasionally led his own ensembles, including Adamantine Vehicle and Sadhana, with Vincent Chancey. Parker has worked prolifically as a sideman and as a leader of bands such as The Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra, In Order to Survive, the William Parker Quartet, and Raining on the Moon, to name a few of the ones that have recorded. Zen played in the Billy Bang Quintet and Roy Campbell’s Pyramid Trio, among others. He also led Umoja – a trio with either Parker, Reggie Workman or Sirone on bass, tenor saxophonist Zane Massey, and sometimes vocalist Milene Bey – in which he could explore his Korean heritage in a jazz context. Their stories all continue, but it is wonderful to have this forgotten chapter in their respective careers restored.

Ed Hazell©2010

All photos courtesy of Jason Hwang except where indicated.